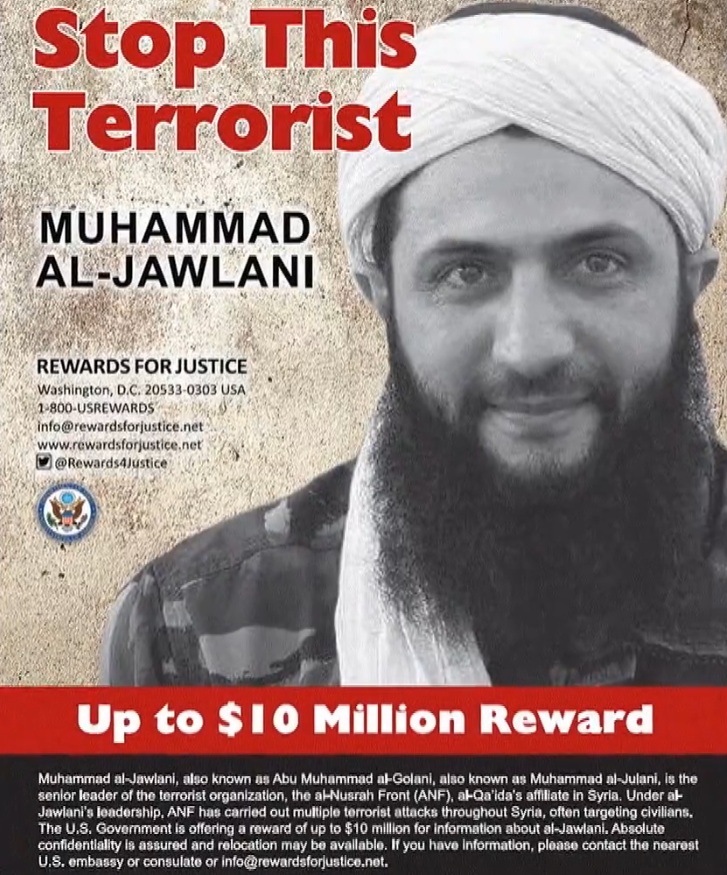

In a striking illustration of instrumentalism and moral fluidity, a recent 60 Minutes segment aired by CBS News introduces the world to Ahmed al-Sharaa — a man once buried in the shadows of terrorism, now stepping into the light of political legitimacy. Just decades ago, al-Sharaa was a senior member of al-Qaeda who went by the name al-Joulani until he entered the presidential palace in Damscus, imprisoned by both U.S. and Iraqi forces, and the subject of a $10 million bounty offered by the U.S. government. Today, he’s not only a free man but a political figure being positioned as a legitimate interlocutor in Syria’s post-war reconstruction. In the segment, host Margaret Brennan sits across from al-Sharaa and discusses his violent past with the casual tone of old acquaintances revisiting youthful mistakes. “We are talking about 25 years ago. I was 17 or 18 years old,” he says, likening his role in a terrorist organization to an adolescent phase.

The casual absolution of his past — on national television no less — reveals far more than just one man’s journey from extremism to influence. It tells a broader story about how the West, particularly the United States, often redefines morality when strategic interests are at stake. There is a long, repeating history of the U.S. government condemning figures as terrorists only to later embrace them when the balance of power shifts. In these moments, labels like “terrorist” or “freedom fighter” lose their fixed meaning and become instead flexible tools of foreign policy. What makes al-Sharaa’s case particularly glaring is not just his past, but how smoothly it has been recast — not through accountability, but through political convenience and media reframing.

This transformation is not unprecedented. History is replete with examples of former enemies turned temporary allies. Yet, watching such a rapid shift unfold in real time — from manhunt to handshake — raises uncomfortable questions about the consistency of values in international diplomacy. The messaging is unmistakable: if you can shift your allegiance or prove yourself useful to Western objectives, your past can be not only forgiven, but forgotten. It’s not so much that people can’t change — many do — but that this redemption seems selectively granted, often at the precise moment when their newfound narrative aligns with geopolitical goals.

Media plays a pivotal role in this process. Rather than challenging al-Sharaa on the weight of his past, CBS’s segment helps smooth the transition from militant to statesman. By focusing on Syria’s future and al-Sharaa’s political rebirth, the story glosses over the cost of his earlier choices — the lives disrupted or ended under the banner he once served. The effect is subtle but powerful: the former terrorist becomes a relatable figure, even a symbol of resilience, while the victims of the past fade from the frame.

What makes this transformation particularly jarring is not just the selective memory, but the ease with which it’s presented. There’s no reckoning, no deeper exploration into the ideology he once subscribed to, or whether its remnants linger beneath the surface. Instead, the audience is invited to accept his past as an awkward chapter in a coming-of-age story — one that conveniently ends with him on the right side of current American interests.

The stakes of this narrative shift are not merely academic. When the West forgives and legitimizes former extremists based on political need, it sends a message — not just to adversaries, but to allies and citizens alike — that justice is negotiable. That terrorism is not an unforgivable crime, but a potential stepping stone to power if the timing is right. It challenges the moral foundations of counterterrorism efforts and invites cynicism about the values the West claims to uphold.

Ahmed al-Sharaa’s transformation might serve American strategy in Syria today; it relveals that the label terrorism is an instrument of the State, far from being the cruel practice that targets civilians for political gains. Today, in the belief and practices of the leaders of the Free World, terrorists have many alliances, and the cost of these alliances may not be fully visible yet. What is clear, though, is this: in the theater of global politics, yesterday’s terrorist can become today’s diplomat — not through reckoning or reform, but through relevance. And when that happens, the lines between redemption and whitewashing become dangerously thin.