Abstract

Nanotechnology has emerged as a foundational scientific domain with wide-ranging implications for medicine, materials science, energy systems, and industrial productivity. This research note examines how sustained, coordinated investment in scientific infrastructure, human capital, and research-to-production integration can enable a country to achieve global competitiveness in an advanced field despite structural constraints. Using Iran’s development of a nationally embedded nanotechnology ecosystem as a case study, the paper analyzes the mechanisms through which large-scale education pipelines, centralized research governance, and deliberate commercialization pathways transformed laboratory science into industrial output and export capacity. The study highlights how scientific depth, rather than external access alone, determines long-term technological performance, and offers insights into how emerging economies can convert fundamental research into durable economic value.

.

Sanctions are designed to exploit dependence. Their strategic logic assumes that modern economies are too embedded in global networks of finance, technology, and trade to function effectively when access is restricted. By denying inputs, sanctions are meant to impose economic pain that translates into political concession. Yet this logic overlooks a critical dynamic: economies do not merely consume technology, they learn. When denial is prolonged and predictable, it can shift incentives away from short-term adjustment and toward long-term capability formation.

Iran’s experience under decades of sanctions illustrates this dynamic with unusual clarity. Rather than treating sanctions as a temporary disruption to be endured or circumvented, Iranian policymakers increasingly treated them as a structural condition requiring permanent institutional response. This reframing altered the objective from restoring access to achieving autonomy. Technological sovereignty, rather than reintegration, became the organizing principle of policy design.

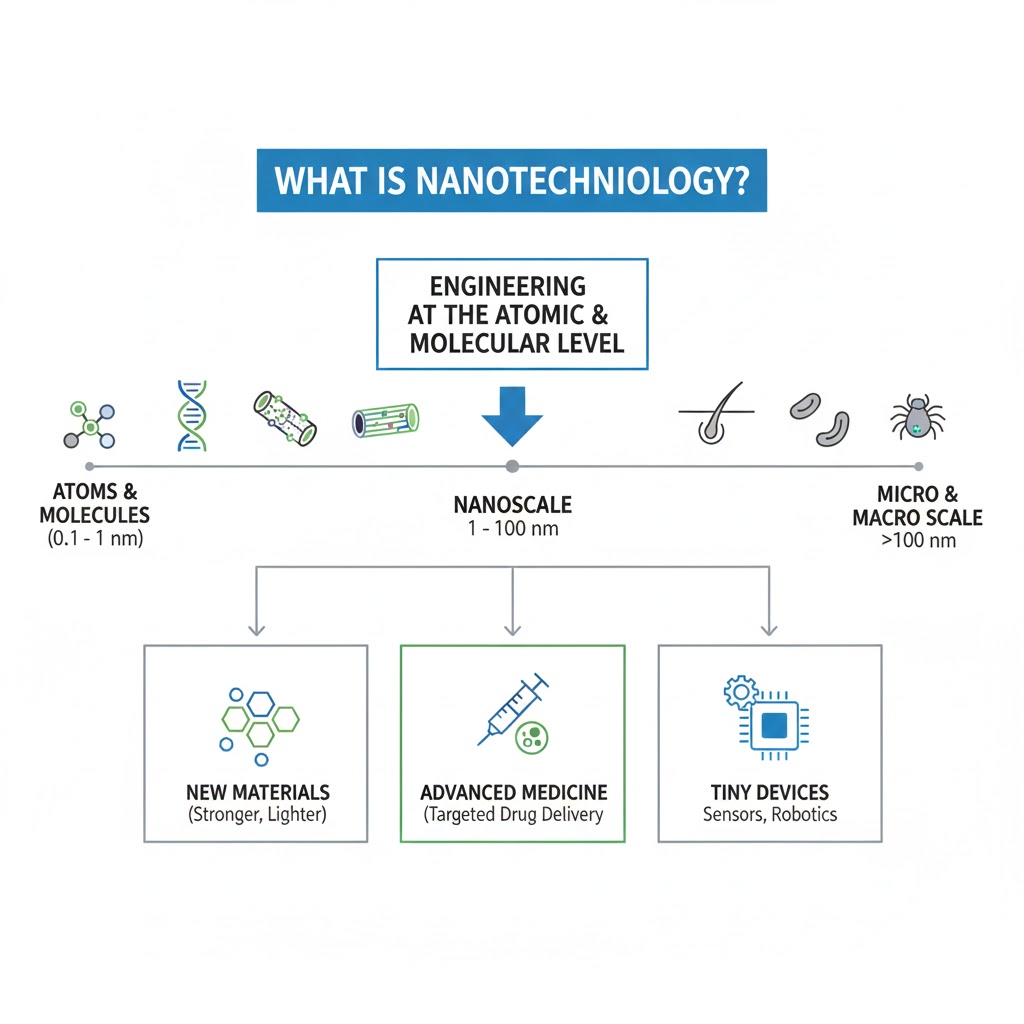

Nanotechnology emerged as a strategic focal point within this broader vision. The field is not confined to a single sector; it underpins advances in medicine, materials, energy, electronics, and industrial processes. Investment in nanotechnology therefore offered compounding returns across the economy. Importantly, it also relied less on heavy physical capital and more on scientific training, making it particularly suited to an environment of financial and trade restriction.

Nanotechnology emerged as a strategic focal point within this broader vision. The field is not confined to a single sector; it underpins advances in medicine, materials, energy, electronics, and industrial processes. Investment in nanotechnology therefore offered compounding returns across the economy. Importantly, it also relied less on heavy physical capital and more on scientific training, making it particularly suited to an environment of financial and trade restriction.

The establishment of the Iran Nanotechnology Innovation Council in 2003 marked a decisive institutional commitment to this path. The council was tasked not with symbolic advancement, but with achieving measurable global standing. Over time, it provided continuity of strategy across political cycles, coordinated funding and research priorities, and aligned educational institutions with national objectives. Research output expanded rapidly, eventually placing Iran among the top global producers of nanotechnology research. More significant than volume, however, was the deliberate refusal to treat publication as an end in itself.

A defining feature of Iran’s approach was its emphasis on human capital as the primary sanctions-resistant asset. Large-scale engagement of students began at the secondary school level and extended through university education and postgraduate research. By embedding nanotechnology education deeply within the national education system, Iran created a broad and resilient base of expertise. This abundance of trained researchers reduced the marginal cost of experimentation and allowed failure without systemic collapse. Knowledge accumulation became local, cumulative, and difficult to disrupt from outside.

Equally important was the engineering of a structured pathway from academic research to market application. In many sanctioned or developing economies, scientific isolation results in a proliferation of research disconnected from production. Iran addressed this gap by institutional design. Academic theses were systematically channeled into applied research programs, which in turn were linked to corporate research and development initiatives. Dedicated commercialization platforms connected prototypes with manufacturers and investors, creating a closed-loop system in which ideas could move predictably from laboratory to product.

The outcomes of this system are visible in the scale and diversity of Iran’s nanotechnology sector. Hundreds of companies now operate in the field, producing thousands of commercial products ranging from industrial materials to medical applications. Patent registrations in US and European jurisdictions signal not only domestic capacity, but competitiveness in external markets. Despite financial and trade restrictions, nanotechnology products have become a source of export revenue, supported by a rapidly expanding domestic market.

The outcomes of this system are visible in the scale and diversity of Iran’s nanotechnology sector. Hundreds of companies now operate in the field, producing thousands of commercial products ranging from industrial materials to medical applications. Patent registrations in US and European jurisdictions signal not only domestic capacity, but competitiveness in external markets. Despite financial and trade restrictions, nanotechnology products have become a source of export revenue, supported by a rapidly expanding domestic market.

These results complicate conventional theories of sanctions. Economic coercion is most effective when it targets consumption-based dependence and when compliance can be achieved before adaptive learning occurs. In contrast, long-term sanctions applied to states willing to invest in education, institutional continuity, and applied research may accelerate precisely the capabilities sanctions are intended to suppress. In such cases, isolation compresses innovation timelines by eliminating alternatives and forcing strategic clarity.

Iran’s nanotechnology trajectory does not suggest that sanctions are costless or that they universally fail. Rather, it demonstrates that their effectiveness is conditional. Where human capital is treated as infrastructure, where policy coherence is sustained over decades, and where learning is systematically translated into production, sanctions lose their coercive edge. Under these conditions, pressure does not merely fail to enforce dominance; it can actively contribute to the emergence of technological independence.

The broader implication is that power in the contemporary international system is increasingly rooted not in access, but in capability. Sanctions deny access. They do not, on their own, prevent learning. When learning becomes the central strategy, economic pressure risks becoming an inadvertent accelerator rather than a constraint.